This week, I’ve been acting as a Visiting Faculty member for a course in tropical biology run by the Organization for Tropical Studies after an invitation from my friend, Darko Cortoras. It’s been six years since I’ve last been in Palo Verde—the last time, again, was as an invited faculty member for a course coordinated by the then-REU coordinator, Scott Walter. And, it’s been three years since I’ve been to Costa Rica; by far the longest period since I was first able to go in 2007 with a tropical ecology course at Kent State.

The primary responsibility I have has been to mentor a brief project with a group of undergraduate students enrolled in the course, but I also delivered a lecture on decomposition in the tropicals and a seminar covering some of the research I’ve done in the wetlands at Palo Verde and beyond.

My students have been fantastic; I think this has been the first time some of them have ever been in a wetland before, and we spend a good 10 hours trudging through the waist-deep water to collect some data on macrophyte community composition. It is encouraging to jump into the much with a group of euthusiastic students who suffer through the uncomfortable heat, bugs, skink, and work with smiles and excitement.

In any case, their project concerns the abrupt change in macrophyte communuity composition across habitat types created by management of the wetland. That is, the wetland is managed to reduce cattail (Typha domingensis) domination of the landscape, and it has been successful in increasing diversity and wetland use by many metrics, including birds and macrophyte species.

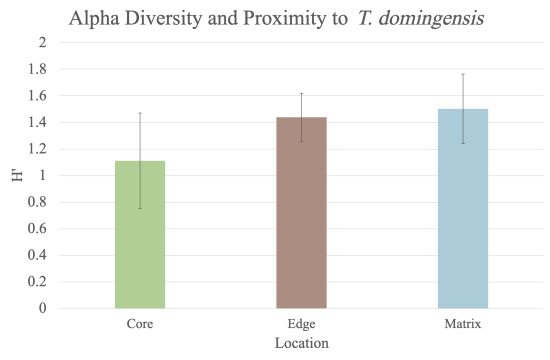

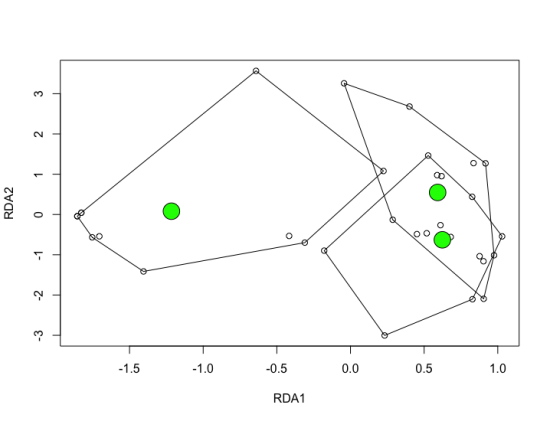

We ran transects at the edge of large patches of T. domingensis, sampling 10 m within the T. domingensis, at the edge of the patch, and 10 m outside. At each sampling point along the transect, students identifed all of the macrophytes within a 50×50 cm quadrant, ranking the top three species, to esimate community composition.

The students were able to demonstrate that macrophyte communities differed within the T. domingensis patches, and the edge of the patches represented an abrupt change in community composition, but communities were similar at the edge and beyond.

These student projects are developed and completed in about two days—an awesomely fast turn around. I think differences between edge and “matrix” or outside habitat could be demonstrated if they had time to measure percent cover of the quandrants using top-down images, which they took but didn’t have time to quantify.

The drive and excitment in developing, collecting data, and presenting their work was excellent; I think they came away from the experience having learned a good amount about the scientific process, wetland macrophyte communities, and teamwork. I’m happy I was able to guide them and a bit sad that I’m now headed back to the desert in Grand Junction… although I think Amos will appreciate my return.